EDP Systems For Success

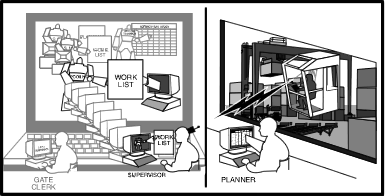

Figure 9

Pooling Usually a terminal operator will assign a group of handling equipment to a pool. There is a pool of handling equipment for the gate operation and there is a pool of equipment assigned to each quay crane operating against a vessel. Some of the pools will be under-utilized, relatively idle, and some will be over-utilized which creates a bottleneck in the operation. These pools are based on historic terminal management techniques. There are several problems with pools:

- The maximum size of the pool is restricted to the number of pieces of equipment that can be managed by the single supervisor in charge.

- Equipment cannot be moved quickly from one pool to another and back again, without confusing the supervisor in charge of the pool.

- The size of the pool is normally set to the peak requirement of the particular operation. When equipment is assigned in this manner, even a naive observer will notice that for the most part the terminal handling equipment does not appear to be moving.

In this type of pooled operation, equipment requirements are set for the peak rate of the entire terminal; not the peak rate of each operation.

Back to the Future

It is clear that the evolutionary direction of computer systems is toward more comprehensive computer-directed systems; from paper, to simple passive recording systems, to computer-directed operations. This means that each year the computer will increasingly assist terminal management in directing the handling equipment in the terminal. The reason for this is simple. Simulations used to evaluate the computer-directed techniques discussed in this paper show 30% overall productivity improvements in handling equipment use. Even though there has been some effort to fully automate container handling equipment [reference 7], except for the occasional elimination of the longshore equipment operators, a computer- directed operation achieves all of the productivity of full automation.Historically, the building of computer software is highly labor intensive, requiring a large programmer effort. In the future, this will continue. There is no expectation that any industry innovations on the horizon will fundamentally alter the labor component in any substantial way [reference 8]. In view of this, the more comprehensive programs are expected to intensify the labor component. In addition, the cost of labor to create computer programs is expensive and is expected to continue to rise, at least in the United States, as a labor shortfall continues to occur over the next decade [reference 9]. As computer programs become more complicated, the cost and time to produce them will become unpredictable, and consequently quite risky. Even recently, several of the best known industry methods for estimating programming time and cost have been shown to be in error in actual use by 200% to 600% [reference 10].

In spite of all of this risk, terminal operators still maintain a preference for developing their own software. This is understandable as every operation is unique and it is difficult to locate programmers who understand that a terminal is something other than a data entry device for the computer. Unfortunately, like youngsters, each terminal manager must be burned on the stove of software development. When this happens, the thoughtful manager will discover value in already written computer systems and disregard the preference to develop their own. Several companies offer such turn-key packages for marine terminals wishing to purchase the experience of others [reference 11,12]. These systems can usually be modified to meet the terminalŐs unique needs without the inherent risk of custom software development. However, properly selecting software with a structure that can be modified to fit each terminal's unique circumstances requires care [reference 13]. It is the task of management to understand the development history of computer systems in the context of the marine terminal industry and focus on a system that avoids the pitfalls of the past and leapfrogs the terminal squarely into a solid, productive, and efficient future.